Due Diligence Leadership in Lagos Real Estate: Legal, Technical, and Financial Tracks That Investors Can Trust

Introduction

In Lagos, due diligence is not a checklist you tick at the end. It is the leadership function that makes every other part of the transaction possible. Title must be verified against the public record, not just against what a seller presents. Surveys must be charted at the Office of the Surveyor-General to rule out encroachment, acquisition, or overlap. Planning and building-control status must be confirmed with LASPPPA and LASBCA, especially for multi-storey and waterfront projects. And the financial model must be tested against what the project can actually permit and register, not what was drawn in an early concept. When these tracks run in parallel, capital moves. When they don’t, even a good asset becomes unbankable

We frame due diligence around three questions. Legally: does this seller have the capacity to transfer, and will the transfer be recognised by Lagos State once consent, stamping, and registration are completed? Technically: does the land and structure conform to Lagos’ planning regime and to the technical standards of special districts such as Eko Atlantic, so that construction, utilities, and service-charge operations can run without dispute? Financially: do the cash flows, costs, taxes, and statutory payments support the returns being pitched to UHNW, family offices, or institutional investors? A leadership-level diligence pulls these answers together in a way that boards and lenders can audit.

This article sets out how we run diligence on high-value Lagos assets so that nothing material is left for the buyer to “discover” later: how we lead the legal track through CTCs, consents, and registration; how we run the technical and regulatory track through LASPPPA, LASBCA, and (where relevant) Eko Atlantic protocols; and how we use financial diligence to confirm that the business case survives sensitivities on costs, FX, and timing.

Legal diligence leadership: title, capacity, consents, and registration reality

Legal diligence in Lagos has one job: prove that the seller can transfer an interest today, and that the interest you buy can be perfected tomorrow. Everything else (valuation, bankability, even pricing) hangs on that.

Start with the instrument and the chain.

We collect the root document (typically a C of O or a Governor’s Consent on an earlier transfer) and pull Certified True Copies from the Lands Bureau so we are not relying on scanned or altered versions. We then reconstruct the chain: from original state grant to every subsequent assignment, mortgage, or sublease. Where any link in the chain lacks consent, we flag it and either (i) require retroactive consent, or (ii) build a gap-cover step into closing. This is the point at which we also check that the interest being sold is the same interest described in the survey and in the offer.

Chart the survey, don’t just sight it.

We submit the survey to the Office of the Surveyor-General for charting to confirm coordinates, to rule out government acquisition, and to detect overlaps with adjoining parcels. A clean charting report is one of the fastest ways to lower execution risk and to convince a buyer’s bank to stay on timetable. Where charting throws up queries, we either re-survey or adjust the transaction per the actual metes and bounds.

Match the deal to the consent regime.

Under the Land Use Act, any further assignment or mortgage of a property that already has a C of O requires the Governor’s Consent. Lagos publishes the documentary requirements (deed, title, survey, tax clearance, photographs), and the Bureau runs charting and assessment before issuing an approval and bill. Timelines vary, typically several weeks to a few months depending on file completeness and follow-up, so we treat consent as a dated condition, not a background assumption. For estate or free-zone assets (e.g. Eko Atlantic), we duplicate the step with the developer: get the estate’s no-objection, confirm technical compliance, and secure recognition of lender/buyer step-in.

Test capacity and authority.

If the seller is an individual, we confirm identity, marital status where applicable, and spousal consent if the property is matrimonial or jointly acquired. If the seller is a company, we review CAC filings, resolutions authorising the sale or charge, and any board or shareholder approvals required by its articles. If the seller is a trustee or estate, we confirm appointment, powers of sale, and any court or beneficiary consents. This is often what makes institutional or diaspora buyers comfortable: they can see that the person signing can actually bind the owner.

Close the fiscal posture.

We check ground rent, land use charge, and development levy where applicable. Unpaid charges in Lagos can block consent or registration, so we quantify arrears and either (i) make the seller clear them before completion, or (ii) escrow the amount and clear immediately after filing. That single step removes one of the most common sources of delay.

Document for registration.

We draft and review the instruments (deed of assignment, deed of sublease, deed of mortgage/charge) with registration in mind: correct property description, survey references, parties’ full details, execution clauses matching corporate or marital status, duty computation language, and recitals that match the chain. We also make sure specimen signatures and photographs are in the file so the registry can process without re-query.

Why this is “leadership” and not admin

Because this legal track runs first, the technical and financial teams are not building models on incomplete or uncertain interests. It also lets you walk into a negotiation with a factual position, not an opinion, which is what institutional capital expects.

Technical and regulatory diligence: survey, planning/building approvals, and Eko Atlantic protocols

Technical diligence in Lagos is mainly about one question: can what is on ground, or what is proposed, be approved, connected, and certified by the relevant authorities without future dispute. To answer that, we run the planning track (LASPPPA), the building-control track (LASBCA), and, if the asset sits in Eko Atlantic or another estate-controlled environment, the estate/FTZ track, all at the same time.

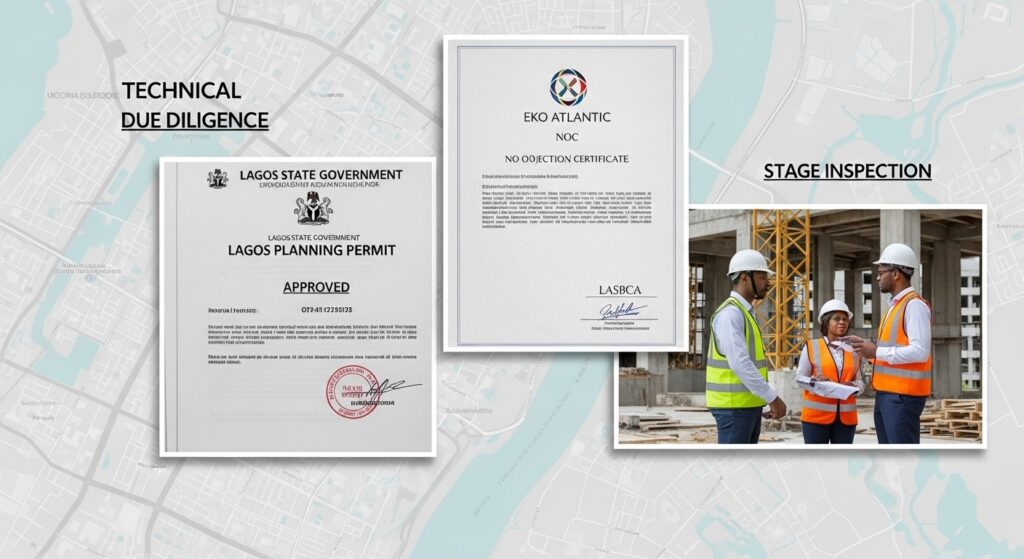

1. Planning compliance (LASPPPA).

We confirm that the current or proposed use matches the zone. The Lagos State Physical Planning Permit Regulations 2019 set out permitted uses, setbacks, airspaces, building coverage, and right-of-way protections. Any change of use, increase in height, or redevelopment must pass through the permit process. We obtain the issued permit or, where development exists without one, we verify whether regularisation is possible and on what terms. A project that cannot be regularised may still be sellable, but it will not be financeable on institutional terms.

2. Building control and stage certification (LASBCA).

For built assets, we check whether LASBCA was invited for stage inspections and whether a Certificate of Completion and Fitness for Habitation is in the file. The agency now publishes clear guidance on green stickers, stage inspections, and completion certificates; deals that ignored this step will have to cure it, and that takes time. We also confirm structural integrity on multi-storey assets and whether any contraventions or demolition notices have been issued. This is the point where we reconcile drawings with what is actually built. If the building deviates materially from the approved plans, we quantify the compliance path and bake it into the closing timetable.

3. Estate and Eko Atlantic protocols.

Eko Atlantic operates an extra layer: developer consent for transfers, technical no-objection for design and services, contractor registration, and service-charge compliance. The city also expects recognition of lender or buyer step-in, so we obtain that letter and add it to the diligence file. Without these, a buyer may own the interest in law but still be unable to connect to power, water, or services. We treat these documents as conditions for completion or, at minimum, for final escrow release. Other private estates in Ikoyi and VI have similar rules (clear service-charge arrears, apply for transfer, follow façade or signage guidelines); we confirm them and quantify the cost.

4. Utilities and infrastructure interface.

We check the real status of power, water, drainage, and road access. In some corridors, connection fees, transformer levies, or road-setback conditions must be cleared before expansion or change of use. Where the project depends on estate-provided infrastructure (Eko Atlantic, some VI/Oniru pockets), we collect the current schedule of charges and confirm that the buyer will be recognised as a paying occupier. This avoids disputes at handover.

5. Reporting it for the investor file.

All of the above is written up in a technical diligence report with three colours: compliant, curable, and non-compliant. Curable items get costs and timelines. Non-compliant items get business decisions: walk away, re-price, or re-scope. That report sits next to the legal report so committees see the full regulatory picture in one place.

Financial diligence: model, statutory costs, sensitivities, and investment committee packs

Financial diligence connects what the lawyers and engineers found to what investors were promised. It answers three questions: what does this project really cost once Lagos statutory items and estate charges are added, what does it earn in plausible market conditions, and how robust are the returns if time or FX moves against us.

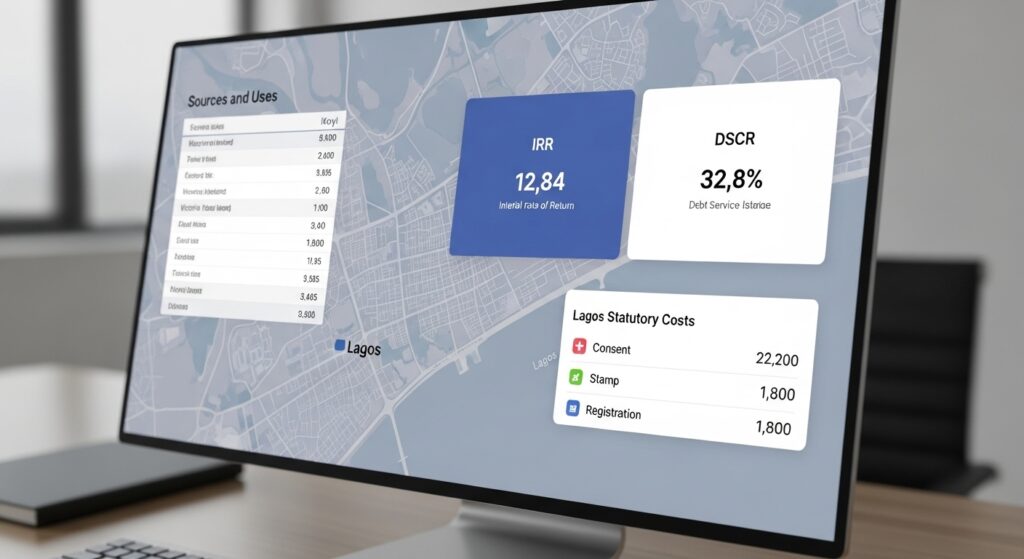

Build from statutory reality, not brochure numbers

We start with a bottom-up cost sheet that includes: purchase price, Governor’s Consent, stamp duty, registration, capital gains tax (if we are on the sell side), ground rent and land use charge arrears, estate or service-charge clearances (for Ikoyi/VI estates and Eko Atlantic), connection or infrastructure levies, and professional fees. These are booked as real cash items with expected timing. This alone can move project IRR because many Lagos deals underestimate government and estate costs by 2–4 percentage points of value.

Reconcile the model to what is legally and technically buildable

The architect’s concept does not always match what LASPPPA or the estate will approve. We adjust gross floor area, saleable/leasable area, parking, and uses to the approved or approvable scheme. That revised scheme feeds the revenue side of the model. Where there is an existing income asset, we replace “aspirational” rents with actual rent rolls, WALE, arrears, and SNDA status, and we discount any units that rely on non-compliant uses until regularisation is confirmed. For Eko Atlantic, we add the service-charge regime and utilities pricing into operating costs so the NOI is realistic.

Run the sensitivities committees ask for

We run at least four cases:

- Base case (approved scheme, current statutory costs, current rent/sales assumptions);

- Cost overrun case (5–10% construction or remediation increase, plus slip in statutory timelines);

- Time/absorption case (3–6 month delay in consent/registration or in sales velocity);

- FX/rate case (naira costs rising vs a dollar or hard-currency investor, or local rate uptick hitting finance costs).

From these we derive IRR, equity multiple, DSCR/ICR (for financed assets), and break-even occupancy or sales. Where the project is intended for UHNW or family-office co-investors, we also show the “cash yield” view for income phases, because that is how many of them measure success.

Document for the investment committee

The financial diligence note is short but referenced: sources and uses table, key assumptions with source documents in the VDR, output metrics (IRR, EM, payback, DSCR, LTC/LTV at completion), and a risk-and-mitigant table that aligns with the legal and technical reports. Each assumption in the note links to an artefact: title CTC, survey charting report, LASBCA certificate, estate NOC, QS budget, or valuation. The IC is not asked to “trust”; it is invited to verify.

Why this level of financial diligence matters

When the financial track is built on the legal and technical tracks, investors are not surprised by Lagos-specific costs, lenders see that statutory timing is priced in, and sponsors can negotiate from a position of fact. That is what turns a compelling asset into a financeable transaction.

Conclusion

Due diligence leadership in Lagos is about sequencing and visibility. Legal must prove the seller can transfer and that the interest can be perfected. Technical and regulatory must prove that the asset, as built or proposed, can be approved, connected, and certified by the right authorities or estates. Financial must prove that, after statutory and estate costs, the project still delivers the returns presented to UHNW, family offices, or institutions. When these three tracks run in parallel, the investment committee sees one coherent story, not three competing versions of reality.

This is especially important for Eko Atlantic and estate-controlled assets, where developer or estate consents, technical NOCs, and service-charge clearances sit alongside Lagos State requirements. By pulling those into diligence early, we protect pricing, keep lenders on timetable, and give overseas or cautious capital confidence that what is being sold is what will be registered.

The outcome is simple: fewer re-trades, faster credit decisions, and Lagos assets that remain bankable across cycles.