Negotiating Prime Lagos Transactions: Acquisitions, Disposals, and Land Deals That Close

Introduction

In Lagos, the real negotiation does not happen when price is mentioned. It happens when title is tested, boundaries are charted, statutory costs are counted, and timelines are aligned with Governor’s Consent and registration. In Ikoyi, Victoria Island, and especially assets touching Eko Atlantic, buyers and sellers are not only negotiating value; they are negotiating risk, sequencing, and reputation. A deal that looks attractive on paper can become unbankable if the chain is broken, if the survey overlaps, or if the fiscal load (consent, CGT, stamp, registration) was not priced into the offer.

Our negotiation method is therefore evidence-first. We verify root of title, check survey and charting at the Office of the Surveyor-General, confirm whether the land falls under acquisition, and pull Certified True Copies to see what has actually been registered. Where there is a C of O and a resale is involved, we factor in the cost and time of Governor’s Consent, which in Lagos typically runs 30–90 working days depending on completeness and follow-up. That timing affects deposit, possession, and longstop clauses, so it must be settled at the table, not after signing.

We also treat negotiation as multi-variable, not “price-only.” On acquisitions we trade certainty for price: sellers get a clean, time-boxed closing and we get verifiable documents, escrow releases tied to consent and registration, and full disclosure of service charges or estate rules where the property sits in a managed development or a free-zone-oriented district like Eko Atlantic. On disposals we control information, use NDAs and data rooms instead of ad hoc forwarding, and insist that offers state assumptions on title, permits, and statutory fees. That keeps offers comparable and protects the seller from re-pricing after due diligence.

This article explains how to negotiate Lagos transactions in a way that a lender, an institutional buyer, or a cautious family office will respect. We will cover how to prepare the deal room before you talk numbers, how to structure terms so consent, stamping, and registration are actually achieved, and how to close land deals where community, estate, or free-zone interests must be recognised.

Preparing the negotiating table: evidence, assumptions, and statutory costs

Lagos deals go wrong when parties negotiate on assumptions instead of verified facts. So we front-load verification and make it part of the negotiation pack.

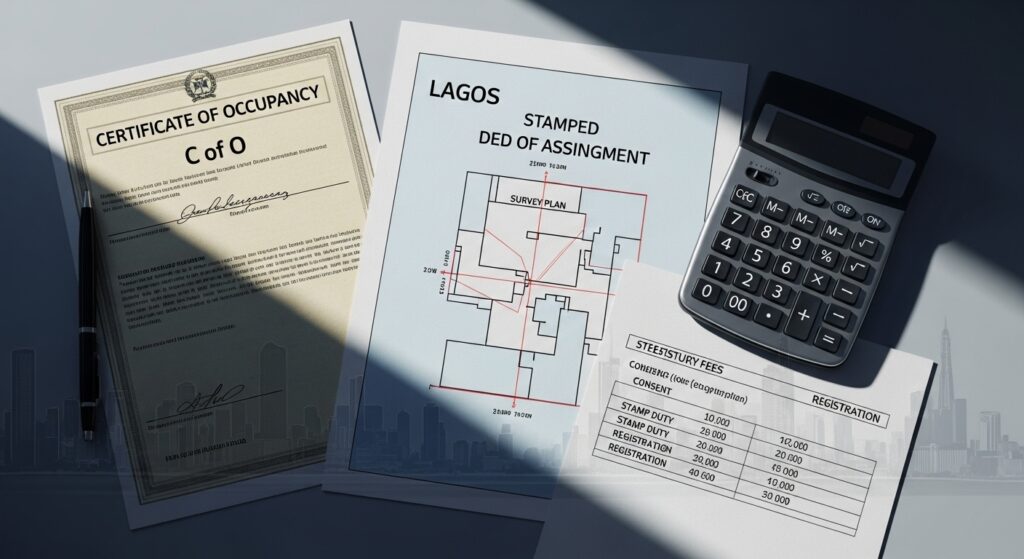

Start with what is being sold.

We collect the root of title (C of O, Governor’s Consent, Deed of Assignment, or, in estate-controlled environments, the developer’s allocation/sublease) and obtain Certified True Copies from the Lands Bureau. This tells us what has actually been registered, not what the seller remembers. We then chart the survey at the Office of the Surveyor-General to confirm coordinates, to see if the land sits on government acquisition, and to detect overlaps or double surveys. This is non-negotiable in Lagos and should be done before any offer is priced.

Price in the real statutory load.

Many transactions are re-priced because the parties did not agree up front who pays for consent, stamp duties, registration, and capital gains tax. Current Lagos practice typically includes: consent fee around 1.5% of property value, stamp duty (often 1.5%), registration (around 0.5%), and capital gains tax on the seller’s gain. If the property is in a high-value district (Ikoyi, VI) or is a corporate-held asset, there may also be development levies or estate dues to clear. We list every cost in the term sheet and allocate it clearly so there is no “hidden” 3–4% appearing at perfection.

Lock the regulatory context.

We confirm planning and building-control status (especially for improved properties) and, where the asset is inside Eko Atlantic, we add the free-zone and estate layer: developer consent for assignment or charge, technical NOC, utilities/service-charge standing. If these are not obtained or at least acknowledged, the buyer’s lender may not fund, which will lead to renegotiation or delay.

State assumptions in the offer.

Our offers always state: subject to clean title and CTCs; subject to positive survey charting; subject to Governor’s Consent (or developer recognition, in Eko Atlantic); subject to settlement of statutory charges up to completion; and subject to delivery of vacant possession or agreed tenancy schedule. This framing prevents re-trades later, because both parties saw the conditions from the start.

Why this helps negotiations.

When evidence, statutory costs, and regulatory posture are visible, negotiation can focus on value, timing, and risk allocation instead of discovery fights. It also makes offers comparable if the seller is speaking to more than one buyer.

Structuring terms for Lagos realities: consent, escrow, and timing

Once facts and costs are clear, the negotiation shifts to execution. In Lagos, execution fails for three predictable reasons: consent is slower than assumed, funds move before perfection starts, or possession transfers before regulatory and fiscal clearances. We structure terms to remove those three risks.

Consent-aware timelines

We treat Governor’s Consent (or, in estate-controlled/FTZ assets, developer consent and technical NOC) as a project, not a form. The agreement states who will apply, what documents will be supplied (CTCs, survey, tax items, photographs, corporate documents), and how long each stage should take. We add a realistic window for queries. Where consent is a condition precedent, completion is tied to the issuance of consent or, at minimum, to proof of filing with receipts. Where the parties agree to complete before consent, we insert a time-bound obligation to perfect and a fallback (title-gap cover or retention) if perfection is delayed.

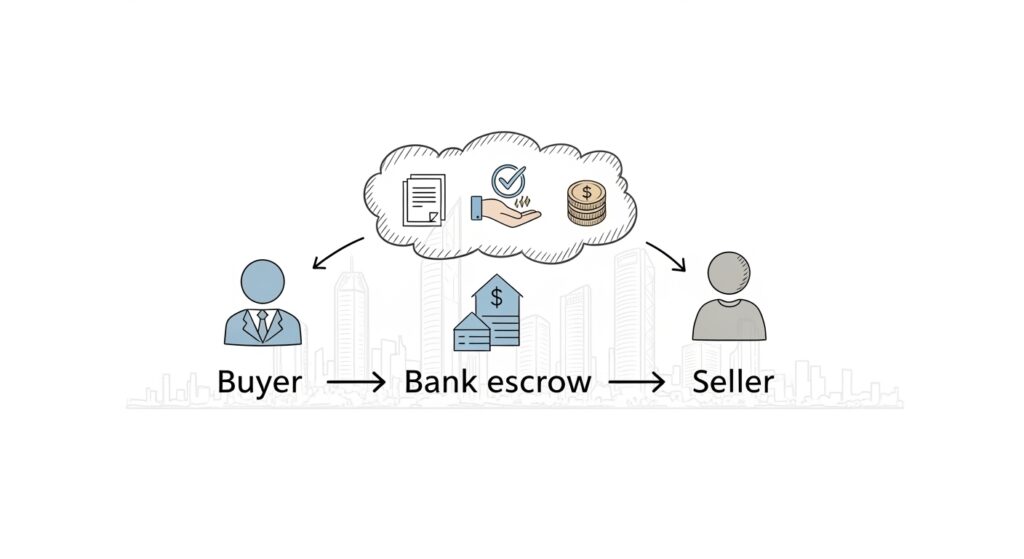

Escrow and milestone payments

We do not let full consideration move on day one. The SPA or Deed of Assignment is paired with an escrow agreement with a bank that will only release funds when objective conditions are met: execution of instruments, evidence of duty payment, filing for consent, delivery of vacant possession or agreed tenancy documents, and provision of all title originals. For land deals, we often stage payments: initial deposit on signing, substantial tranche on filing for consent, and final tranche on registration. For improved assets, we may add a technical/estate clearance stage to ensure the buyer will actually be connected to power, water, and estate services. This structure protects buyer capital and signals seriousness to the seller.

Possession vs completion

We separate physical possession from legal completion. Early possession is granted only after the buyer has paid the agreed deposit, executed all instruments, and provided indemnities for occupation. Legal title passes on fulfilment of conditions (consent, stamping, registration). This is especially important where the buyer wants to start site investigations or early works before perfection; the agreement must define liability, insurance, and restoration obligations in that period.

Allocating statutory and estate charges

We insert a fiscal schedule in the agreement listing: consent fee, stamp duty, registration, capital gains tax, land use charge, ground rent, estate or service-charge arrears, and any special levy. The agreement states who pays what and when. If an amount is not yet assessed, we agree a retention in escrow to cover it. This prevents the common situation where a seller demands the buyer pays arrears that were incurred before the effective date.

Longstop and termination

Because consent and registration can slip, we add a longstop date after which either party may terminate if the other has not met its obligations. To avoid abuse, a party that caused the delay (e.g. by not supplying documents or not clearing arrears) cannot rely on the longstop. This gives both sides a clean exit if the transaction becomes impossible without forcing litigation.

Why this is persuasive in negotiation

When you present terms this way, you are not being difficult; you are de-risking the seller’s exit and protecting the buyer’s capital. Institutional buyers, family offices, and lenders recognise the sequence and will often prefer your offer to a higher but loosely drafted one.

Special cases: Eko Atlantic, estate-controlled assets, and land with community history

Not every Lagos asset follows the classic “C of O → Deed of Assignment → Governor’s Consent → Registration” path. Three categories regularly require a modified negotiation structure: (i) assets in Eko Atlantic, (ii) properties inside private or corporate estates with their own rules, and (iii) land with a community or family history that was only later regularised.

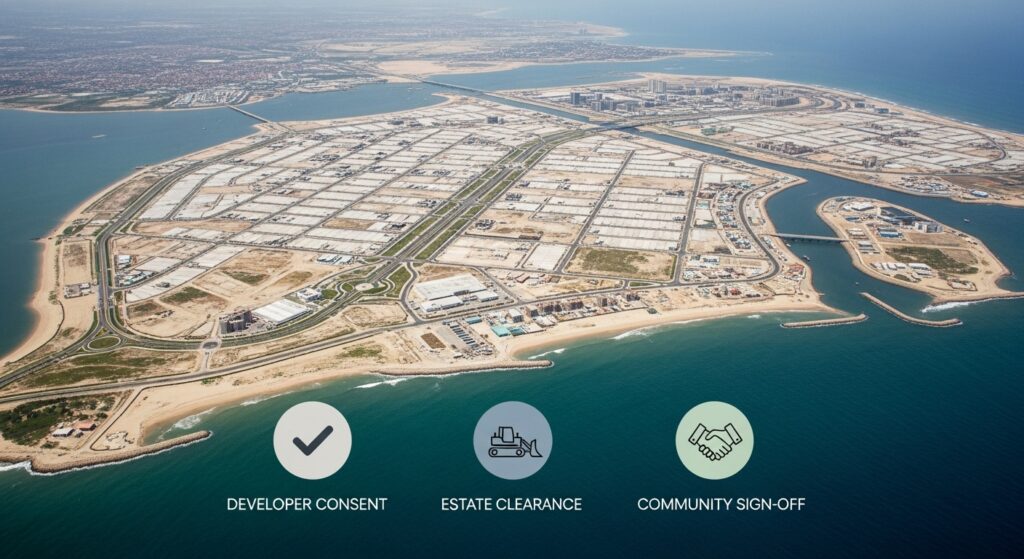

Eko Atlantic and other FTZ-oriented assets

Here, you are negotiating inside a dual framework. The buyer is not only taking an interest; they are taking that interest subject to the city developer’s covenants, technical standards, utilities interface, service-charge regime, and, often, free-zone protocols. So the SPA must do four extra things:

- Identify precisely what is being transferred (allocation, headlease, sublease, development agreement) and confirm that it is transferable.

- Make the developer’s consent and technical no-objection a condition to completion or, at least, to final escrow release.

- Secure the developer’s recognition of lender or buyer step-in, so financing will be enforceable.

- Confirm estate/service-charge standing and the rules that will bind successors.

We attach those documents to the data room before we discuss price. That way, the buyer is not surprised later when the developer insists on its own consent fee, fit-out rules, or design review. It also keeps the price credible, because the buyer has visibility on all cash calls attached to ownership.

Estate-controlled and serviced developments

Ikoyi and VI have a number of assets where title is clean but operations are governed by an estate or service manager. In those cases, negotiation must address arrears, transfer fees, service-charge rules, and facility standards. We obtain statements of account from the estate manager, agree who will pay arrears, and make the issuance of an “estate clearance” or “welcome” letter a closing item. If the buyer intends to change use, signage, or occupancy profile, the SPA should state that estate approval is required and that the seller makes no promise on that point. Otherwise, the buyer will try to reopen price when the estate pushes back.

Land with community or family history

Where the land originated from a family, community, or chieftaincy grant and was later perfected, we negotiate with memory as well as with law. We do three things:

- Confirm from the registry that the state’s grant (C of O or Governor’s Consent) is in place and unchallenged.

- Identify outstanding community or family undertakings that were never fully performed (honorarium, resettlement, fencing, employment undertakings).

- Decide whether to clear those undertakings before closing, or to escrow a small amount until the community issues a fresh letter of non-objection.

We make community sign-offs documentary, not oral. Where the community insists on being present at handover, we add a protocol to avoid disruption on the day and to protect the buyer’s quiet possession.

Why these cases must be negotiated differently

In all three scenarios, the buyer is taking an interest with one or more “upstream” actors still in the picture (developer, estate manager, community, or zone authority). If those actors are not acknowledged and documented in the SPA, they will reappear at the worst time: when the buyer seeks to connect to power or water, to resell, or to finance. By pulling them into the negotiation early, we protect price, timeline, and reputation.

Conclusion

Negotiating acquisitions, disposals, and land deals in Lagos is less about haggling and more about sequencing. When title, survey, statutory costs, and regulatory posture are verified before price is agreed, the negotiation becomes straightforward. When payment is routed through escrow and tied to consent, stamping, registration, and (for Eko Atlantic or estate assets) technical and service-charge clearances, capital is protected and sellers still get certainty. When special stakeholders such as developers, estate managers, or communities are brought into the documentation instead of being left “outside,” the deal remains bankable long after closing.

This is the standard we use with institutional buyers, UHNW clients, and family offices. It is factual, document-driven, and aligned with how lenders evaluate risk. The result is fewer re-trades, faster completions, and assets that remain financeable and transferable across cycles.