Portfolio Strategy for Private Wealth and Corporates: Using Lagos Prime Real Estate as a Spine

Introduction

For serious capital, Lagos real estate is no longer a one-off “property play.” It is a structural decision inside the wider portfolio. Ultra-high-net-worth investors, family offices, and corporates now have to answer three questions very clearly:

- What role should Lagos prime assets actually play in our portfolio: income, growth, inflation hedge, or a mix of all three?

- How much exposure is appropriate, given already high allocations to alternatives and real assets in most sophisticated portfolios?

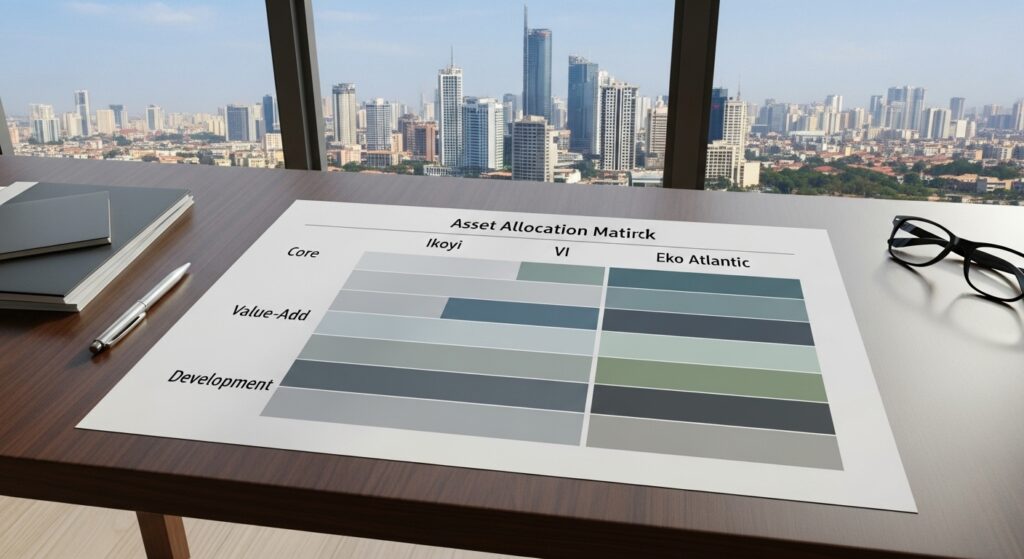

- Within that allocation, how do we balance Eko Atlantic, Ikoyi, and Victoria Island across core income assets, value-add, and development risk?

Global data shows that family offices and UHNW investors are already heavy allocators to alternatives, with direct real estate sitting as a significant share of those allocations. At the same time, Nigeria has just passed through a period of sharp inflation and FX volatility, while reforms are gradually stabilising the macro environment. That combination makes the question of “how” to hold Lagos risk, not just “whether,” more important than ever.

Our own practice treats Lagos prime real estate as a portfolio spine rather than a speculative side bet. For private wealth, that means linking allocations to long-term liability needs, liquidity horizons, and currency exposure, not just to “deal flow.” For corporates, it means deciding whether to sit in owner-occupied assets, long-income structures, or flexible lease positions, and how to avoid over-concentration in a single corridor or asset type.

In this article, we look at portfolio strategy from that vantage point: how we define the role of Lagos prime real estate inside a broader balance sheet, how we build a practical allocation framework for private wealth and corporates, and how we blend core, value-add, and development exposure across Eko Atlantic, Ikoyi, and VI without losing discipline on risk, liquidity, or governance.

Defining the role of Lagos prime real estate in private and corporate portfolios

The first mistake we see is treating every Lagos asset as if it serves the same purpose. It doesn’t. A fully-let Grade A office in Victoria Island, a core residential block in Ikoyi, and a development plot in Eko Atlantic all sit in the same city but play very different roles in a balance sheet.

For private wealth, we start with liabilities and lifestyle, not with “opportunities.” What long-term cash needs has the family already committed to: education, healthcare, succession obligations, charitable pledges, legacy projects? What currencies are those liabilities in? If a family already carries heavy naira exposure through operating businesses, Lagos prime real estate should often be positioned as a real-asset anchor with disciplined income and carefully controlled development risk, not as an unconstrained speculative lever. That usually means a spine of core or core-plus income assets in established micro-markets, with a limited allocation to value-add or development that is clearly capped.

We also separate roles inside the portfolio. Some assets are there to pay (stable cash yield from blue-chip or institutional-grade tenants). Others are there to grow (value-add repositioning, selective Eko Atlantic exposure, redevelopment in improving corridors). A smaller slice might be there to option (early positions in emerging schemes or special situations). When we label each asset explicitly, it becomes easier to decide how much leverage is sensible, how much volatility is acceptable, and how to report performance to principals in a way that matches expectations instead of surprising them.

For corporates, Lagos real estate sits in a different conversation. The core question is whether the company should own, co-own, or lease its critical locations. Owner-occupation in Ikoyi or VI can stabilise occupancy costs and hedge against inflation, but it also concentrates capital in a single geography and sector. Long-income sale-and-leaseback structures can release capital for core business while preserving operational control, but only if lease covenants and renewal mechanics are drafted to survive more than one management team. We therefore define, in writing, whether a particular asset is strategic (mission-critical HQ or operations), financial (held for return), or opportunistic (legacy property or surplus land that should be recycled).

Once that role is clear, questions about Eko Atlantic versus Ikoyi versus VI become technical rather than emotional. Eko Atlantic might take a higher-risk, higher-return development or corporate flagship role; Ikoyi often suits long-term residential and mixed-use income; VI may be better for corporate and institutional office exposure. The portfolio view forces discipline: no single corridor, tenant, or project should be allowed to dominate the Lagos risk the family or corporate is carrying.

Building an allocation framework for private wealth and corporates

A Lagos portfolio becomes coherent when allocation is written down, not improvised. We use a simple framework built around exposure limits, risk buckets, liquidity bands, and governance.

A. Exposure limits: how much Lagos, how much real estate

For private wealth, we start at the top of the balance sheet. Global private-wealth studies consistently show real estate (direct + funds) taking a significant share of assets for UHNW families. The question is not whether to hold Lagos prime, but how big that slice should be relative to:

- Operating businesses (often already Nigeria-heavy)

- Offshore financial assets (listed securities, funds, alternatives)

- Other real assets (global real estate, private credit, infrastructure, etc.)

We typically set:

- A cap on total Nigeria real estate as a percentage of net worth (for example, 15–30%, depending on existing business concentration).

- A sub-cap on Lagos prime, so that one city does not exceed a defined share of total real estate.

- Within Lagos, a cap per corridor (Ikoyi, VI, Eko Atlantic) and per asset type (income vs development), to avoid “silent concentration” in a single theme.

For corporates, the lens is different:

- Cap owner-occupied property as a percentage of total assets or equity, to prevent the operating company turning into an unacknowledged property fund.

- Set a limit on Lagos exposure if the underlying business is already Lagos-centric, to avoid doubling down on the same geography.

- Decide whether surplus or legacy real estate is “non-core” and should be monetised or repurposed on a timetable.

B. Risk buckets: core, value-add, development

Once exposure limits are set, we assign each Lagos asset to a risk bucket, with target ranges:

- Core / core-plus

- Stabilised buildings with diversified, creditworthy tenants, long leases, and modest capex.

- Typical in Ikoyi and VI prime blocks or well-leased mixed-use.

- Used as the “bond” of the Lagos sleeve: lower volatility, steady income, moderate leverage.

- Value-add

- Assets requiring repositioning: lease-up, refurbishment, re-tenanting, or modest change of use.

- Can sit in Ikoyi side streets, older VI stock, or early Eko Atlantic income assets.

- Higher target returns, tighter business plans, and stricter capex governance.

- Development / opportunistic

- Ground-up or heavy redevelopment in Eko Atlantic or changing corridors.

- Highest return targets, capped allocation, and the strongest demands on governance, QS control, and financing discipline.

For a typical sophisticated family, a Lagos sleeve might look like: 50–70% core/core-plus, 20–40% value-add, 0–15% development, depending on age, income needs, and global diversification. For a corporate, development risk is usually much lower unless the company is in the property business itself.

C. Liquidity bands and tenor

Real estate is illiquid; Lagos prime even more so in stressed markets. We therefore map each asset to a liquidity band and ensure the portfolio has enough staggered exit options:

- Short/medium term (0–5 years): projects to be developed, stabilised, and exited; legacy non-core assets scheduled for sale.

- Medium/long term (5–10+ years): strategic income assets, trophy holdings, or corporate HQ sites.

For private wealth, we tie these bands to real dates: children’s education cycles, anticipated business exits, or generational transitions. For corporates, we link them to strategic plans, debt-maturity profiles, and potential restructuring windows.

D. Governance as part of allocation

Finally, allocation is enforced by governance, not enthusiasm. We formalise:

- An investment policy statement (IPS) for the Lagos sleeve, stating exposure caps, risk buckets, and approval thresholds.

- A decision body (family investment committee or corporate real estate committee) with clear roles for internal and external advisers.

- A requirement that every new Lagos deal shows, on page one, where it sits in the framework: corridor, risk bucket, effect on exposure caps, expected liquidity horizon, and governance implications (board seats, JV terms, or covenants).

If a proposed project breaches the framework (for example, too much development risk in Eko Atlantic or over-concentration in one tenant), the committee must either (i) reject or resize it, or (ii) consciously amend the policy. Nothing slips in “by exception” without being named.

Blending Eko Atlantic, Ikoyi, and VI across strategies

A Lagos allocation becomes powerful when each corridor does the job it is best suited for, instead of every project trying to be everything at once.

Eko Atlantic: controlled development and flagship exposure

Eko Atlantic is purpose-built: engineered land, controlled urban design, and a strong focus on Grade A office, luxury residential, hospitality, and mixed-use. That does not make it a generic “Lagos” proxy. It sits closer to a thematic allocation:

- For private wealth, we treat Eko Atlantic as a concentrated growth sleeve. It suits (i) carefully structured development or co-development with strong governance, or (ii) selective flagship exposure in completed, income-producing schemes.

- For corporates, it is logical for headquarters, regional hubs, or client-facing locations where brand and infrastructure matter, provided the company is comfortable being part of a still-maturing district.

In both cases, we cap Eko Atlantic exposure as a share of the Lagos sleeve and keep leverage conservative. Governance, QS control, and estate compliance are non-negotiable. The goal is to let Eko Atlantic express growth and branding, not to let it silently dominate the family or corporate risk profile.

Ikoyi: long-duration residential and mixed-use income

Ikoyi remains one of Lagos’ strongest residential and mixed-use districts, with established high-income demand, consular and institutional presence, and limited truly comparable substitutes. That makes it suitable for the core and core-plus buckets:

- Stabilised or near-stabilised residential blocks, serviced apartments, and mixed-use schemes aimed at upper-income households and long-stay occupiers.

- Select neighbourhood commercial and social infrastructure where tenancy is sticky and land is scarce.

Here, we lean into long leases, diversified tenant profiles, and close attention to building condition and facility management. For private wealth, Ikoyi often carries the “bond-like” income side of the Lagos book: moderate growth, strong preservation. For corporates, Ikoyi might house senior staff accommodation or lower-density workspaces. The risk is not usually vacancy; it is overpaying at entry or underfunding capex, which leads to a slow slide in relevance.

Victoria Island: office, mixed-use, and liquidity

VI remains the most recognised commercial address in Lagos, with a deep history of corporate and financial occupancy and an evolving stock of mixed-use and hospitality assets. It plays well in core, core-plus, and value-add strategies:

- Well-leased office and mixed-use buildings with diversified corporate tenants sit in the core/core-plus bucket.

- Older or mispositioned stock suits value-add through re-tenanting, reconfiguration, or ESG-driven upgrades.

For private wealth, VI is a practical way to gain income exposure to corporate and professional tenants without concentrating everything in one sector or micro-location. For corporates, VI is often the default HQ or major office, which creates a different risk: the operating business and the real estate can become overly correlated to the same district.

Avoiding the classic concentration traps

Across these three corridors, the traps repeat themselves:

- One project becomes the portfolio. A single Eko Atlantic development quietly grows to 60–70% of the Lagos allocation. We counter this with hard caps by project and by corridor, and by linking any new Eko allocation to a reduction elsewhere or an increase in offshore diversification.

- One tenant defines the income story. A trophy VI or Ikoyi building ends up with one anchor paying most of the rent. We limit exposure to single tenants as a percentage of income and require SNDA language and strong covenant checks before signing.

- One exit window is assumed. Models assume all value-add and development assets will be sold in the same 2–3 year window. We stagger business plans so at least one viable exit is available in most market conditions: refinance, partial sale, JV recapitalisation, or full disposal.

- FX and naira risk stack on top of each other. Families already heavily exposed to naira businesses then load heavily into naira-only real estate returns in the same corridors. We measure Lagos real estate as part of Nigeria risk, not separate from it, and pair it with offshore assets and appropriate currency hedging or structuring where feasible.

Pulling it together

When we blend Eko Atlantic, Ikoyi, and VI with written exposure limits, risk buckets, and liquidity bands, the Lagos sleeve starts to behave like a designed portfolio rather than a collection of deals. Eko Atlantic can carry high-governance growth and flagship projects. Ikoyi anchors defensive residential and mixed-use income. VI offers institutional-grade commercial and mixed-use exposure, plus value-add opportunities. Together, they create a spine that supports, rather than distorts, the wider balance sheet.

Conclusion

For serious private and corporate capital, Lagos prime real estate should not be a collection of favoured assets. It should be a designed sleeve inside a wider portfolio. That starts with clarity of role: which holdings are meant to pay steady income, which are meant to grow value, and which are optionality or flagship risk. Once that is written down, exposure limits, risk buckets, and liquidity bands become tools, not theory.

Within that framework, Eko Atlantic, Ikoyi, and Victoria Island each have distinct jobs. Eko Atlantic is a focused growth and flagship corridor that requires strong governance, capped exposure, and conservative leverage. Ikoyi is a natural anchor for long-duration residential and mixed-use income, where preservation and quality of management matter more than headline yield. VI offers diversified commercial and mixed-use exposure, plus credible value-add opportunities, but must be managed so one tenant or sector does not quietly dominate the book.

When we blend those corridors under a single policy, supported by a standing committee and disciplined reporting, Lagos stops being a binary “on/off” bet. It becomes a spine that supports long-term objectives: predictable cash flow for families, capital efficiency and flexibility for corporates, and assets that remain financeable and tradeable across cycles.