Distressed Real Estate and Workouts in Lagos: How We Rescue Value for Owners and Lenders

Introduction

In Lagos, prime real estate does not fail in a single moment. It drifts. Interest capitalises quietly, consents and registrations stall, contractors slow down, tenants leave, arrears build up, and a good address starts to underperform its postcode. By the time a facility is non-performing on the lender’s books or sponsors are in open dispute, most of the damage has already been done to value, reputation, and timelines.

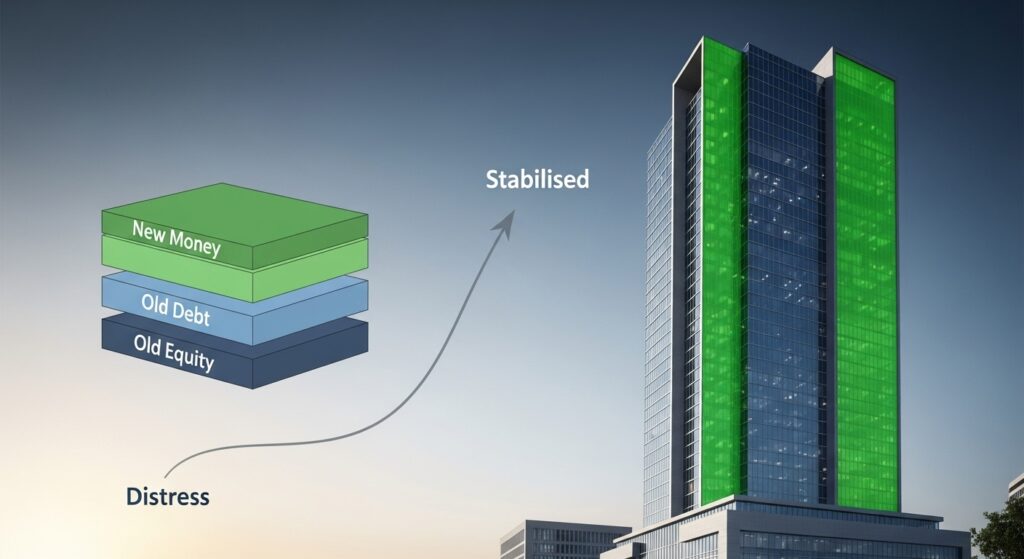

We treat distressed assets and workouts as a separate discipline, not as an extension of ordinary asset management. The objectives are different. For owners, the priority is to protect equity from being wiped out in a disorderly enforcement or forced sale. For lenders, the priority is to stabilise the collateral, restore income, and achieve recovery without years of litigation or reputational fallout. For incoming capital, the priority is to enter on terms that reflect risk, with governance that prevents a repeat of the original failure.

Our method starts with clarity. We establish a factual baseline of title, consents, physical condition, income, debt, and litigation. We then design a path that is realistic in Nigerian law and banking practice: standstill where it is justified, cash sweeps and governance changes where they are needed, equity top-ups or sponsor buy-outs where there is still a business case, and, when necessary, an orderly enforcement or recapitalisation instead of a fire sale. In special districts such as Eko Atlantic, we add estate and free-zone considerations, because city management and service-charge standing often determine whether an asset can even be repositioned.

In this article we set out how we approach Lagos workouts in practice: how we stabilise a distressed asset, how we structure negotiations between sponsors and lenders, and how we design exits and recapitalisations that are credible for private wealth, family offices, institutions, and banks that must answer to regulators.

Stabilising the asset: facts, cash, and control

In any Lagos workout, the first priority is not negotiation. It is stabilisation. Until we know exactly what we are dealing with, “restructuring” is just a word.

A. Establish a clean factual baseline

We build a short, unforgiving fact pack:

- Title and perfection

- Pull CTCs for all title documents and registered charges.

- Confirm whether Governor’s Consent, stamping, and registration have been completed for both ownership and security.

- In estate or Eko Atlantic assets, add developer/estate consents and technical NOCs.

- Survey and compliance

- Re-chart the survey with the Office of the Surveyor-General to rule out overlaps, acquisition, or encroachment.

- Check planning permit and LASBCA status: is the structure compliant, were stage inspections done, is a completion/fitness certificate obtainable?

- Debt and security

- Reconcile facility agreements, drawdowns, interest, fees, and arrears.

- Confirm all security actually exists as registered: legal mortgages, debentures, assignments of rents, guarantees.

- Income and operations

- Build a current rent roll or sales schedule: who is in occupation, who is paying, what is vacant.

- Obtain estate/service-charge and utilities statements to see arrears and disconnection risk.

- Litigation and encumbrances

- List all suits, injunctions, caveats, and competing claims.

This is usually the first time all parties see the same reality on one page.

B. Stop the bleed: immediate cash and risk measures

We then apply triage to cash and risk:

- Ring-fence current income

- Redirect rents or sale proceeds into a controlled account (often escrow) on which lender and sponsor agree a temporary waterfall: essential operations, insurance, minimum maintenance, and agreed debt service.

- For unfinished projects, ensure buyer deposits are no longer mingled with general cash and are protected while a solution is being worked out.

- Protect the asset physically

- Secure the site or building, update insurance, and address obvious safety issues.

- For multi-let assets, communicate with tenants early to prevent departures and reassure them that utilities and services will be kept running.

- Freeze non-essential leakage

- Stop non-critical capex, related-party payments, and unapproved disposals.

- Require that any new obligation above a set threshold is co-signed by a workout committee or the lender’s representative.

At this stage, we are not promising a full cure; we are buying time without losing more value.

C. Clarify who is in charge (and who is not)

Distress usually exposes gaps in governance. We therefore:

- Confirm who legally controls the SPV or holding company (board, shareholders, debenture holder with crystallised security).

- Establish a workout steering group: key sponsor reps, lender reps, and independent advisers (legal, QS/technical, financial).

- Document what decisions require joint sign-off during the workout period: leases above a threshold, sale of units, new borrowing, major construction changes, settlement of litigation.

If a receiver, administrator, or similar enforcement officer is already in place, we fold this into their mandate and ensure they are briefed on estate/Eko Atlantic rules, tenant sensitivities, and existing sale contracts.

D. Triage the problem: business, capital, or governance?

Before talking about term sheets, we classify the distress:

- Business-case issue: demand was mis-read, pricing is wrong, the scheme or mix is mis-positioned, or operating costs are structurally too high.

- Capital-structure issue: leverage too high, tenors too short, currency mismatched, or covenants too tight for the asset’s risk.

- Governance/execution issue: poor oversight, weak contractor management, diverted cash, or key permits and consents neglected.

Most troubled Lagos assets are a combination of all three, but one is usually dominant. That diagnosis determines whether we are looking at a restructure and stabilise, a recapitalisation with new money, or an orderly exit.

E. Decide whether the asset is rescuable on its current path

Finally, we ask a blunt question: is there a viable project or income asset once cash, time, and realistic valuations are applied?

- If yes, we move towards standstill, cure plans, and governance reset in the next phase.

- If not, we design an exit or enforcement that minimises value destruction and reputational risk.

Either way, the stabilisation phase gives lenders, owners, and new investors a coherent base from which to decide, instead of reacting to rumours and partial information.

Negotiating with lenders and sponsors: standstill, cures, and governance resets

Once the asset is stable, the real work is getting everyone to move from positions to solutions. In Lagos, that usually means putting structure around three ideas: time, money, and control.

A. Standstill that earns its keep

A standstill only makes sense if it buys measurable progress, not just silence. We document it, usually as a short agreement or side letter that:

- Freezes new enforcement for a defined period (for example, 90–180 days).

- Locks no new indebtedness, no asset disposals, and no related-party payments without lender consent.

- Requires weekly or monthly reporting: cash position, receivables, QS or progress updates, status of permits and consents.

- Sets hard triggers that end the standstill automatically (breach of reporting, unapproved payments, new litigation, or failure to hit agreed milestones).

That way, the bank can show its credit committee and regulators that it is managing, not ignoring, the problem.

B. Cure ladders: who pays, when, and for what

We then agree a cure ladder so everyone knows what happens when numbers are offside:

- Operational fixes: cost control, re-basing of service providers, repricing and re-letting, more disciplined collection.

- Cash sweeps: excess cash after essential opex and minimum capex goes to debt service or arrears reduction.

- Equity cures: sponsors inject fresh cash (or accept conversion/dilution) to restore DSCR, cost-to-complete coverage, or covenant headroom.

- Structural cures: maturity extension, amortisation re-profile, or limited covenant re-set where justified by a robust business case.

Equity cures are time-bound and evidence-based: funds must hit an agreed account by a set date, and the cure only “counts” once ratios are restored on a signed, updated model.

C. Governance resets: who drives the recovery

Distress is often a governance failure. As part of any serious workout, we revisit control:

- Board changes: add one or more independent directors agreed by lender and sponsors, with clear mandates around reporting and oversight.

- Reserved matters: tighten decisions that require consent during the workout (new leases above a threshold, capex, settlements, professional appointments).

- Monitoring rights: give lenders observer rights at board and key project meetings, plus direct access to QS, facility managers, and sales agents.

- Cash control: formalise controlled accounts, dual signatories, and approval processes for non-routine payments.

In some cases, a receiver-manager or similar enforcement officer is appointed but instructed to prioritise stabilisation and sale or recapitalisation at value, not a rushed auction. The point is to align control with the party best placed to preserve value, while respecting legal rights.

D. Negotiating the restructuring perimeter

We decide what is in scope for the restructure:

- Only the distressed facility and related security, or

- The entire capital stack (senior, mezzanine, shareholder loans), and

- Whether trade creditors, contractors, and key service providers will be brought into any standstill or rescheduling.

For complex structures, we often propose an intercreditor or restructuring term sheet that sets priorities, standstill rules between creditors, and how any upside from recovery will be shared. This reduces the risk of one aggressive creditor derailing the process.

E. Communication with tenants, buyers, and the market

While lenders and sponsors negotiate, the asset still has to live. We put a simple communication plan in place:

- Reassure tenants and buyers that services will continue, that their leases or contracts remain valid, and that they will be kept informed of any operational changes.

- Make sure estate managers, utilities, and Eko Atlantic city management know who to deal with and who can sign.

- Keep public messaging factual and minimal to avoid panic or reputational damage.

Handled well, this keeps income flowing and prevents a second wave of distress from avoidable vacancy.

Designing exits and recapitalisations that actually close

Once everyone sees the same numbers and a standstill is in place, the question becomes simple: do we fix this capital structure, or do we hand the asset to new money under controlled terms? We design that choice so it can be executed inside Nigerian legal and banking realities, not just in a spreadsheet.

A. Map the viable paths up front

We narrow options to a short list that a credit committee or investment committee can actually approve:

- Restructure and hold

- Same owners, same lender, but with new terms: extended tenor, re-profiled amortisation, cured arrears, tighter governance.

- Works where the asset’s business case is intact and the sponsors are willing (and able) to inject fresh equity and accept more oversight.

- Sponsor-led recapitalisation

- Existing sponsors bring in new equity or quasi-equity (family office, UHNW, PE/real estate fund) to pay down debt, finish works, or reposition the asset.

- Lender stays in place, but debt is resized and covenants are reset against a realistic business plan.

- Third-party take-out or JV

- A new investor acquires the asset or the project company outright, or enters as JV partner with majority control.

- Existing lenders are refinanced or partially taken out; legacy equity may roll a small stake or exit entirely.

- Orderly enforcement and sale

- Where the economics no longer support a rescue, the lender enforces security and sells the asset or shares in a controlled process, often with the help of a receiver/manager.

- The emphasis is on preserving value and documentation quality for the next owner, not on speed for its own sake.

We test each path against three filters: recovery for the lender, survivable outcome for sponsors, and attractiveness to new capital.

B. Redevelop the business case, not just the term sheet

Before locking in any recapitalisation, we redo the business case as if we were a new buyer:

- Revisit positioning and pricing: does the scheme need to be re-scoped, phased, or re-targeted (for example, smaller unit sizes, different tenant profile, or mixed-use rebalancing)?

- Re-test costs and timelines with a fresh QS view, including inflation, FX, and supply-chain realities.

- Rebuild lease-up or sales strategies with conservative assumptions and visible pipelines.

Only when that revised case produces credible returns do we frame term sheets. Otherwise, a restructure simply postpones default.

C. Structure new capital with clear priority and control

For recapitalisations, the new money comes in only if its place in the stack is unambiguous:

- Priority

- New senior or super-senior debt needs clear ranking, security, and repayment waterfalls.

- New equity or preferred equity needs documented cashflow priority (if any), exit mechanics, and tag/drag protections.

- Control

- Board seats, veto rights on budgets, capex, disposals, and further borrowing.

- Information rights: monthly packs, QS reports, covenant dashboards, and direct access to key advisers.

We memorialise all of this in updated shareholders’ agreements, intercreditor deeds, and security documents so there is no conflict between old and new arrangements.

D. Design sale and enforcement processes that protect value

If the decision is to exit, we avoid improvised auctions. Instead, we:

- Prepare a data room with full legal, technical, and financial materials so bidders can move quickly and with fewer discounts.

- Agree a sale mandate and process: timeline, marketing channels (often discreet), qualification criteria for bidders, and clear rules around NDAs and access.

- For enforcement sales, ensure the receiver/manager or charge holder follows statutory requirements and best practice on valuation and marketing, so the sale can withstand challenge and so that serious buyers (family offices, funds, institutions) are comfortable bidding.

Where possible, we run a dual-track for a short period: recapitalisation if a credible investor steps up on agreed terms, enforcement sale if not.

E. Close the loop with documentation and post-deal stewardship

Whichever path is chosen, we insist on a clean closing file:

- Updated facility agreements, security documents, and corporate approvals for restructures.

- Signed sale/SPA with clear statements about arrears, consents, estate or Eko Atlantic standing, and transition of operational contracts.

- A short lessons-learned memo to sponsors and lenders: what went wrong originally (business case, capital, governance), and what protections are now in place to avoid repetition.

For recapitalised assets, we also schedule the first 12 months of post-deal governance: board calendars, reporting dates, covenant tests, and site/tenant review cycles, so the workout does not quietly slide back into old patterns.

Conclusion

Distress in Lagos real estate is rarely a single bad decision. It is a series of small failures in information, cash discipline, and governance. Workouts only start to work when all three are put back in order. First, stabilise the asset: one shared factual baseline on title, consents, debt, income, and litigation, combined with immediate controls on cash and physical risk. Then, negotiate time, money, and control in a structured way: documented standstill, clear cure ladders, and governance resets that put competent decision makers in charge of the recovery. Finally, choose and execute a path that can actually close in this market: restructure and hold where the business case is still sound, recapitalise with new money where fresh equity and better oversight can restore value, or run an orderly enforcement and sale where recovery, not rescue, is the rational objective.

Handled with that discipline, distressed assets in Ikoyi, VI, and Eko Atlantic do not have to become write-offs. They can re-enter the market as bankable projects, credible income assets, or clean slates for new capital, instead of lingering as permanent problems on a balance sheet.